The following perspectives were to be presented at the March 2020 100th annual conference of the Association of College Unions International (ACUI), in collaboration with Orok Orok of Prairie View A&M University. The conference was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Randall Knight is an Associate Principal at MHTN Architects. He has nationwide experience serving a diverse list of higher education clients, in planning and designing student life facilities.

At MHTN, we are curiously exploring and sensitively seeking greater understanding of the complex dynamics of diversity and how design can lead to more enriching futures for all of us. The narratives and experiences of diverse and underrepresented communities are all around us and we have had the valuable opportunity to work with higher education professionals and students who are making a difference on the front line of inclusivity initiatives. The following perspectives, grounded in many years of design experience, seek to build momentum in our efforts to follow their example and do better.

Colleges and Universities should be places where students and faculty from diverse backgrounds come together to learn, set aside preconceptions, and collaborate. The confluence of these social dynamics engenders the foundational experience of Higher Education. Institutions seeking to enhance student experience and foster diversity innovation need to understand how planning and design can impact outcomes. Creating environments to welcome and promote diversity requires sensitivity to design factors that influence perception and inform interaction.

1) Power of Perception

Our understanding of space and light have psychological implications: compression/release, dim/bright, rank/fresh. These conditions stimulate positive and negative responses. Our senses are linked to the qualities of space and the “feel” of that space subsequently impacts our ability to connect with others. Our perception of an environment can be subconsciously imprinted onto our relationships.

Student organizations, especially small ones are sometimes shoe-horned into leftover spaces on campus, often of marginal quality and lacking uplifting psychological influences. Consequently, the associations we attribute with a cohort due to their physical environment forms a bias construct. Just as color has generational and gender overtones, so too our perception of environment can be subconsciously imprinted onto our relationships and interactions. Design has the power to modulate perception.

Many institutions do the best possible to support student groups. Capital maintenance is critical, regardless of facility age. While this cannot overcome all psychological shortfalls, it can help minimize disparity between winners and losers.

LGBTQ Resource Center, North Carolina Central University (NCCU). The Student Center will give the Center outside views overlooking the new campus quad.

2) Legacy of Symbols

Institutionalized bias operates on a scale high above the daily individual interactions on campus but has lingering impact on student culture and engagement. Institutional memory can extend beyond decades becoming colored by the symbolic presence of a University’s prized legacy. Symbols become the shorthand of identity, silently appropriating the values and stories of past generations. These are rarely nefarious, but the initial meaning has the unfortunate propensity to dull over time.

It is important to remember who is telling the story. The official account always attempts to reinforce institutional memory, but it is the anecdotes that tend to persist. Institutional stories are intended to unite but can often be blind to the underrepresented; they favor a “champion narrative.” Fortunately, there has been increased positive movement in the tectonic shifting of such narratives, away from misappropriated symbols of winners and losers, towards favoring student voices.

With so much digital messaging, stories are fleeting, and institutional branding has shifted to a virtual world. However, the old analog trappings of past heroes and accomplishments are still enthroned around campuses, seemingly in places of honor, and physical permanence.

Every new planning or design project should be seen as an opportunity to course-correct and ensure that institutional priorities, and the stories created to fund them, are connecting with today’s student experience.

3) Seeing Yourself

New York Times, January 19, 2020.

In the final weeks of 2019, an art exhibit titled “Seeing Newnan” sent ripples through the small community of Newnan, Georgia. Large photographs of every-day residents, were installed as urban murals, revealing an unexpected diversity. There is a liberating truth that can resonate when invisible people are revealed. Similarly, a campus can ignite the spirit of comprehension, tolerance, and shared humanity by consciously choosing to make visible all participants of its dynamic community. When diversity is showcased, it has the effect of celebrating identity, rather than reinforcing.

Many institutions are wondering what is to be done with all the gilded frames in the halls of legacy. Leaning into the discomfort of this conundrum, trying to choose between honoring legacy while embracing a future journey, campus leaders are seeking comprehension. Many institutions are discovering there is nothing lost by broadening the definition of “founder.” The process of making space for new heroes allows for an expansion of the concept of heritage and an acknowledgment that celebrating achievement should not be bound to timelines. Reframing success starts by acknowledging one story at a time.

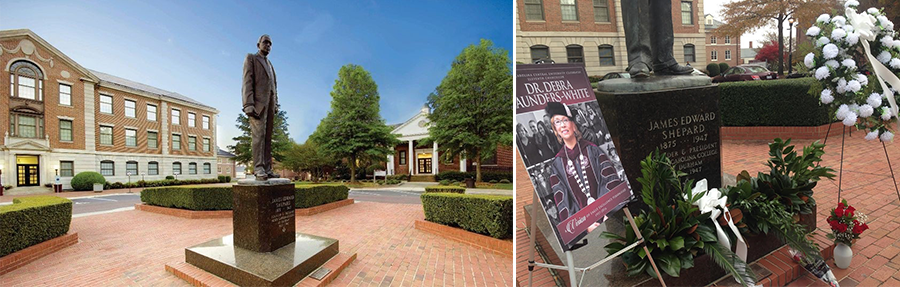

North Carolina Central University Chancellor Debra Saunders-White, memorialized at the feet of University founder James Edward Shepard.

Making space on campus to frame new stories can lead to increased sense of belonging and long-term loyalty. Solid and meaningful connections to the institution will ensue. Conscious efforts to see students and faculty, to make the invisible seen, can find meaningful expression in branding and environmental graphics that highlight untold stories of the past as well as spotlighing nascent and emerging narratives. It is critical to design these installations for easy renovation and renewal.

Environmental Graphics at the University of Utah’s Gardner Commons.

4) Places for Dialogue

Creating space for expression is essential for hearing students. This has been the central role of student unions, nurturing community and dialogue on campus. Flexible meeting space is essential for maximizing the kind of overlaps that lead to community intersections. In MHTN’s design for the new student center at North Carolina Central University a conference room for student collaborations doubles as a dance practice room for intramural stepping teams. With a calculated adjustment in finishes and adjacent storage, the room can become an unexpected place for cultural crossover.

Unintended consequences of certain adjacencies can lead to territorialization, like the placement of all gender restrooms in close proximity with student communities prone to conquest. Foreseeing the potential for contested space is a critical skill in the design and planning team for any facility renovation or new build. Bringing disparate student groups together requires thoughtfulness to ensure underrepresented voices can flourish.

5) An Argument for the Commons

Open lounge environments are critical to the types of interactions that foster cross-disciplinary and diverse engagement. Distributed along primary circulation, accessible to all, they can act as a neutralizer, especially when they are paired with amenities like views out to campus, access to power for mobile devices, and art. The Commons, is an especially evocative and transformational place, where the evolution in public dynamics continues to push campus societies towards more humane and outward expressions of solidarity and unity. This space does not come cheap, but it brings the possibilities of dialogue amplified to a higher scale. Beware that the institutional agenda does not usurp student claims to the Commons. In all things, preserve zones for decompression, the universal need of all students.

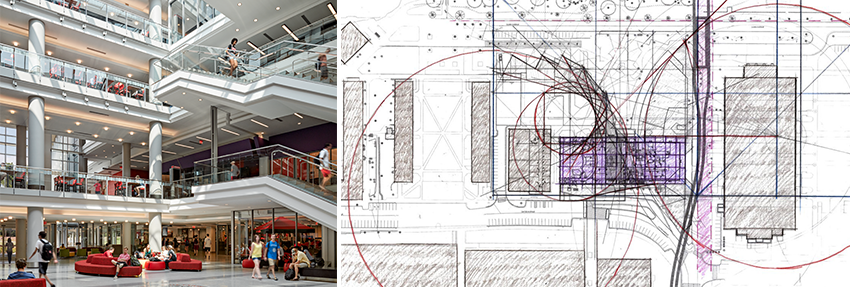

Emory Student Center Commons at Emory University.

6) The Food FIX

Food tends to be forgotten in the efforts on campus to widen circles of inclusivity. Often, food programming is driven by entities that may not share Institutional goals and initiatives, sidelining inclusive menu options in favor of safe, sales-driven offerings. Our cultural identity is tied to our pallet. Campus becomes a home-away-from-home, where students and faculty search for ties to the familiar. Expanding menu offerings is a small effort that welcomes more circles of diversity into dining venues. Any argument to the contrary discounts the reality of students’ natural tendency to explore. Cuisine promiscuity will not change their intrinsic appreciation for familiar flavor but it will open their minds to tasty and valid alternatives; such food diversity threatens no risk to prevailing campus identities.

Emory University’s Dobbs Common Table, having just completed its first year of operation, has transformed the paradigm of campus dining. The broad array of choices not only embodies healthy food culture, but addresses student-requested desire to meet multiple dietary codes and restrictions, from gluten free to kosher, halal to vegan. The design nestles distributed serveries in unique environments that are inspired by iconic Atlanta neighborhoods. Careful planning ensures easy and flexible updating as student needs and tastes evolve.

Campus Dining at Emory Student Center’s Dobbs Common Table, Emory University.

Finally, the coffee effect cannot be underestimated. Just as a watering hole during drought, the culture of the café promotes social equilibriums. Interior design often incorporates most of the key metrics in spatial phenomena mentioned previously, and location drives campus community to the place where one can always receive what they seek.

Student “Flex” Lounges at Emory Student Center, Emory University.

7) Choreographed Adjacencies

When it comes to planning who fits where in a campus building, a complex choreography always ensues. Unfortunately, outcomes are rarely governed by student input. This leads to unintended consequences and perpetuated stereotypes. The team that leads a campus community through planning and design will be most successful in reaching their aspirations for diversity innovation if they listen to students. Students are on the leading edge of change. Any process must empower student voices.

A working design session with NCCU student leaders during their annual leadership retreat.

Location matters. Positioning building occupants in a basement or a penthouse communicates priorities and judgements with far reaching down-stream ramifications. When in doubt, student spaces should be given the prime real estate. The main floor interests always outnumber available square footage, so think vertically and challenge designers to choreograph connections to above and below with creative solutions that can enrich the spatial environment. Be watchful for the potential of design proposals to marginalize.

Whether through alchemy, chemistry, or artistry, designing for diversity is fundamentally rooted in listening. Any institution committed to getting it right must be courageous enough to make space in a design schedule to let architects and designers get to know them. Make space for immersive interactions with students and the unique campus culture and traditions that perpetuate openness, tolerance and unity.

North Carolina State University Talley Student Union