Written by MHTN’s Director of Sustainability, Darrah Jakab, this article was published in

Building Enclosure in August 2022.

The average person spends 90 percent of their time indoors,1, which suggests that the quality of our built environments has significant effects on our overall well-being. Access to daylight and views contribute substantially to the experience of the built environment, influencing cognition, productivity, sleep, and even mood and emotions. Architects have the opportunity and the responsibility to tap into the power of design to positively shape the experience of people and leverage daylight in buildings. When daylighting is prioritized in design, the benefits are many:

- Physiological: a plethora of studies confirm what we intuitively know, that daylight is good for you. Natural light has been found to be superior to artificial light in enabling visual tasks, especially ones that involve fine motor skills and color differentiation. Exposure to daylight is a key factor in regulating sleep and circadian rhythms by regulating melatonin, a hormone that determines a person’s activity and energy levels during the course of a day3.

- Biophilic: as we spend more and more time indoors, any opportunity to reconnect with nature becomes more critical. By providing access to daylight in buildings, we promote biophilia, or the innate connection people have to nature and other living things. When paired with natural materials, patterns, colors, and plants, we further strengthen the biophilic effect in a space.

- Mood-Enhancing / Increased Productivity: access to high-quality daylight has been shown to lessen agitation, improve mood and even ease some pain. Mood changes are likely to affect performance at work and school, suggesting that access to daylight and views directly impacts our ability to perform tasks, retain information, and think creatively3. Daylighting has the ability to affect our perception, job satisfaction and, in effect, when used effectively, boost the bottom line.

- Energy-Saving: in addition to all the benefits related to human wellness, strategically utilizing and controlling daylight can reduce reliance on artificial light during the day and save energy.

As architects, we seek to optimize daylight from the earliest phases of design by first developing a deep understanding of a project’s needs and leverage building orientation and any site opportunities to maximize daylight. By holding Integrative Workshops, we involve project stakeholders, the design team, consultants, and community members to set a project’s goals and targets. These workshops focus on daylighting and building performance. Together we create a shared vision of success, explore possibilities, and can harness collective intelligence to find solutions. When access to daylight is prioritized, spatial organization, seen through the lens of need-for-light, begins to reorient programmatic adjacencies.

Daylighting must always be balanced with building performance. Depending on the building orientation, each façade needs to be carefully considered to provide high MHTN utilizes daylighting analyses, in-house energy modeling, and physical model studies to arrive at the appropriate window-to-wall ratio and develop solar control solutions.

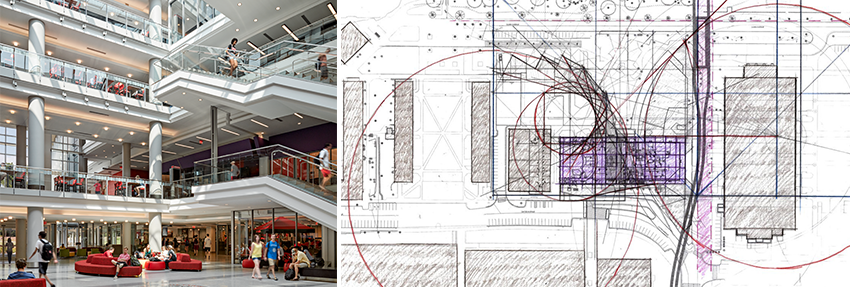

MHTN Architects working through models during an Integrative Design Workshop for the Utah State University Moab Academic Building.

Materials to Consider

When factoring daylight into a project, the light transmittance, reflectivity, color, texture, and light absorptive qualities of all building materials, not just glass, need to be considered. Building materials interact with daylight in different ways at different times of the day. Materials that interact with light in interesting ways can enhance the presence of daylight in a building. Materials that are responsive to light such as highly-textured stone, perforated metal, and even translucent glass can create a dynamic and compelling experience of a building, and their application should be thoughtfully considered during design. Highly reflective materials, however, should be placed appropriately to avoid glare. Glass coatings and tints should be explored and applied judiciously to avoid unnecessary heat gain. Daylighting itself can be treated as a material with all the variation and nuance inherent in controlling natural light.

A classroom inside the Academic Building, integrated with floor-to-ceiling windows that allow natural light to floor the learning environment.

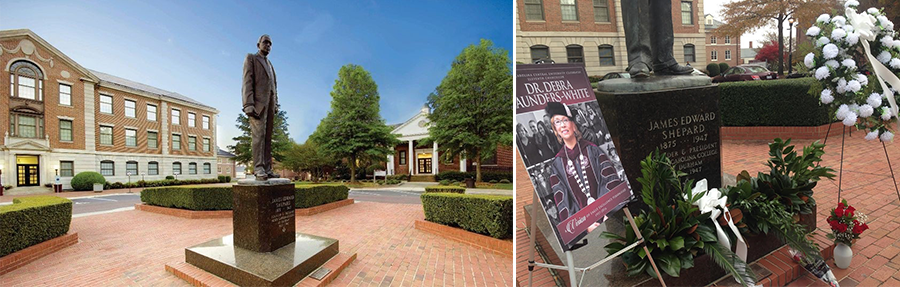

Case Study: Utah State University Moab Academic Building

The recently completed USU Moab Academic Building, located in a highly exposed, rugged site in Southern Utah, is a good example of a project that controls intense solar exposure to create comfortable outdoor rooms. The project leverages optimal building orientation to maximize daylight, capture fantastic views, strategically utilize heat gain during the coldest months, and harness enough solar energy to offset more energy than the building uses over the course of a year. The high desert climate, with its abundant solar exposure, and daily and seasonal temperature swings, presented an ideal opportunity to use passive solar strategies. Window heights and overhangs were optimized to provide the right amount of shading during the summer and exposure during the winter. The long, east-west oriented building takes full advantage of daylight, while clerestory windows bring light to the interior of the building. Classrooms located along the south edge allow for activities to spill out onto a covered porch.

In Closing

Daylighting is a critical piece of architecture and its potential to influence not only the energy performance of our buildings, but the health, well-being, and mood of its occupants is astounding. Architects have a unique responsibility to understand and optimize the ways in which daylight is accessed in buildings. Through a process of integrative design and critical evaluation we can realize the full potential of light, to the benefit of people.

References

- Klepeis, Neil. “The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A Resource for Assessing Exposure to Environmental Pollutants”. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2001. https://indoor.lbl.gov/sites/all/files/lbnl-47713.pdf

- Woo May, MacNaughton Piers, Lee Jaewook, Tinianov Brandon, Satish Usha, Boubekri Mohamed. “Access to Daylight and Views Improves Physical and Emotional Wellbeing of Office Workers: A Crossover Study”. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, Vol. 3. 2021. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2021.690055

- Joseph, Anjali, Ph.D. “Impact of Light on Outcomes in Healthcare Settings”. The Center for Health Design, 2006. https://www.healthdesign.org/sites/default/files/CHD_Issue_Paper2.pdf